This is part of a series with Perfect Earth Project, a nonprofit dedicated to toxic-free, nature-based gardening, on how you can be more sustainable in your landscapes at home.

It can get hot in New Orleans, really hot—and really humid. Climate change can cause drought one month, followed by floods the next. Then there are insect and disease pressures, the proliferation of of invasive plants, frequent epic storms. What’s a historic garden to do? Longue Vue, Perfect Earth Project’s newest Pathways to PRFCT partner, is trying to stay ahead by being proactive with care. And in doing so, they have become a model of sustainability.

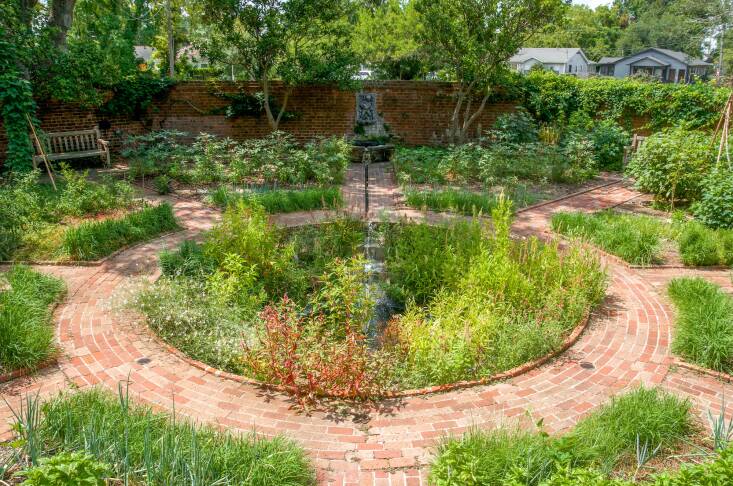

In 2020, the designated National Historic Landmark, designed by pioneering landscape architect Ellen Biddle Shipman in the early 20th century, committed to be toxic-free—no chemical pesticides, herbicides, fungicides or fertilizers. They have banned leaf blowers. They have almost entirely converted from gas-powered equipment to electric (and hope to be 100 percent electric by next year). They leave as much biomass on the property as possible. And they have a dedicated Integrated Plant Care Gardener (what a great title!), Simeon Benjamin, who holistically tends to the garden. Below, he shares tip on how you, too, can maintain a beautiful and toxin-free landscape.

Photography by Diego Bernal for Longue Vue, unless otherwise noted.

1. Inspect your garden weekly.

“Get to know your plants,” says Benjamin. And not just what conditions a plant needs, like hours of sun or water requirements, but also what pests it might be susceptible to. “This way you’ll know what to be on the lookout for.” He starts each day walking through Longue Vue with keen eyes. For home gardeners, he suggests doing this once every week or two, taking notes to keep track of any changes you might see. Look for anything out of the ordinary, like yellowing, brown, or dead leaves, or white powder dusting the foliage. “And don’t forget to look underneath the leaves,” reminds Benjamin. “Many pests like to hide under there.”

2. Monitor the issue.

When Benjamin spots something abnormal, he begins with a wait-and-see approach. “I research the plant to see what pest it could be if I can’t easily identify it,” he says. If a home gardener can’t figure out the problem, he suggests contacting the local cooperative extension to help with the diagnosis. (In Louisiana, Benjamin recommends LSU AgCenter Agent or The Plant Diagnostic Center). “I then monitor the plant each and every week to see if the damage level is enough for me to take action, or if something like a ladybug or lacewing will turn up and take care of it for me,” he says.

3. Begin with the least aggressive course of action.