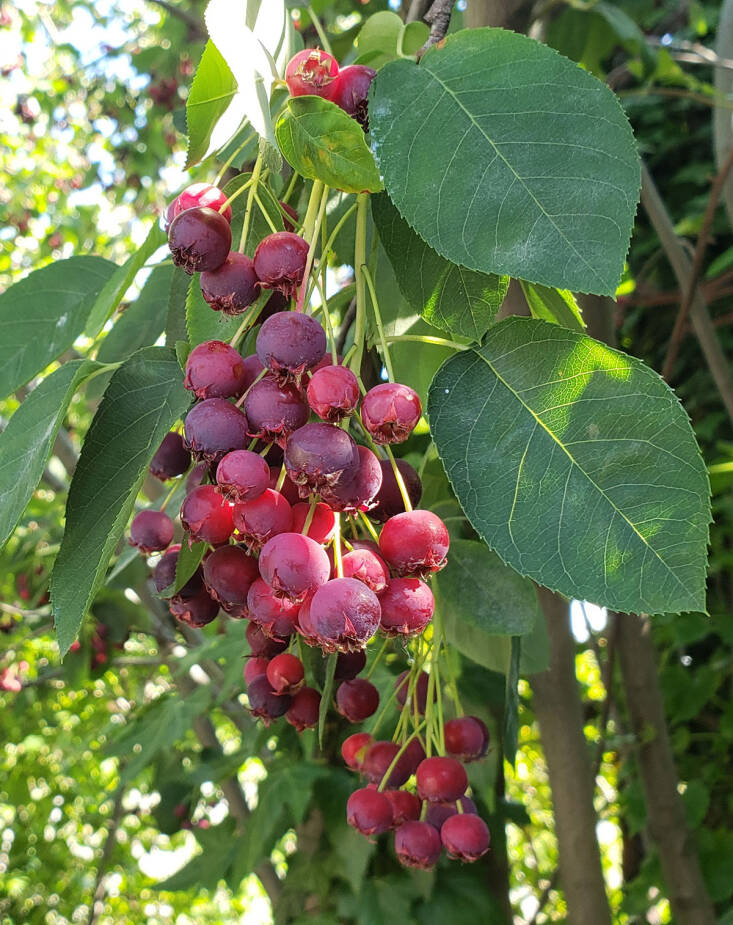

When the perfume of linden trees drifts across New York neighborhoods, I know that it is serviceberry season. Roses have been flowering for weeks, Japanese honeysuckle has erupted. It’s June. Red and purple when ripe, with a faint bloom on their skins, serviceberries hang in clusters from graceful trees. Locally, they are often planted in public landscapes for their spring blossoms, blazing autumn foliage, and graceful resilience in the face of urban adversity. In good fruit-bearing years their branches may bend low, making it easy to reach up and collect the sweet fruit, although often it drops to the sidewalk, untouched. Despite their native status, outstanding flavor, and ability to keep well (refrigerated), serviceberries are rarely seen at market. This is curious, because they are uniquely delicious.

Photography by Marie Viljoen.

Serviceberry is one of a slew of common names for the different species, hybrids, varieties, and cultivars of Amelanchier trees and shrubs. Some common names are associated with a particular species, but mostly they are used interchangeably. So A. arborea, which has dozens of nursery-trade cultivars, is also known as downy serviceberry, juneberry, shadbush, servicetree and sarvis-tree. But it’s hard—even for botanists—to sort out Amelanchier taxonomy, and what you buy at a nursery might not match what the label says. The trees and shrubs tend to hybridize easily, too, making precise identification tricky. They may be multi-stemmed or single-stemmed, they may be tall, or shrubby. What does matter, is how they taste.

Early summer is the time to start sampling.

Most Amelanchier species are native to North America. On the East Coast serviceberries’ pointed, greenly-white buds open to accompany the running of shad (where shad still run), a herring that returns to its birth-rivers to spawn in early spring, giving rise to the names shadblow (blow is old English, from blowan, for blossoms) and shadbush. To Canadians they may be Saskatoon, named from a Cree word for the place where they grew in abundance. Juneberries? It is often the month when they ripen, in Northern summers.

William Clark (of Lewis and Clark) referred to them as “sarvis buries” in his extraordinary travel journal (which inspires equal parts awe and cringe). Native Americans knew serviceberries well. The pounded fruit was an ingredient in regional pemmicans. I have dried the fermented fruit and it is addictively good, tasting like chewy marzipan.

The first serviceberries I tasted grew in a jasmine-scented May garden in the Turkish town of Ayvalik, on the Aegean. Nobody could tell me what they were, only that they were good to eat. I agreed, as I stuffed myself. Back in New York I recognized the same fruit, and suddenly, I saw the trees everywhere. On the Hudson in South Cove Park, in Tear Drop Park, in the then-scrappy parklet* between the Manhattan and Brooklyn Bridges, in Prospect Park, and Central Park. June has become a much-anticipated month.

* Since transformed into the botanically-gleaming Brooklyn Bridge Park, where serviceberries were planted again liberally.

The fruit I ate in Turkey, growing on a sprawling bush, belonged perhaps to the one European species, Amelanchier ovalis (snowy mespilus), which occurs right into central Russia, although the (possibly) American A. lamarckii has naturalized on that continent. And there are Asian serviceberries, too: A. sinica and A. asiatica.